Sometime right after the 9/11 bombings, I had a nightmare: I was doubled over with laughter in a comedy club, when a plane crashed through the roof. It was a pretty straightforward dream, borne of the sorrow, trauma and anxiety of the moment, but it also drove home how wracked with guilt I felt about missing joy as keenly as I did in the weeks following the attacks. Laughing didn't come easy in a stretch when the whole city was crazy with grief, and displays of mourning became briefly, unsettlingly common. I'd never seen as much public weeping before; I'd never been more aware of how inappropriate joy felt, or how deeply I craved it.

I'm grateful that no one involved in the giddy, bubbly revival of Into the Woods gave in to guilt, trauma, grief or anxiety, or even the urge to refer in any way to the current state of things. I'm sure the temptation was there: fairytales perpetuate precisely because their broad strokes fit just about any cultural moment with ease, and we're mired in a pretty dark one to which most live productions have chosen at least a passing nod. Also, any musical that deigns to reflect the entirety of human existence, including the whole spectrum of emotions, practically demands at least a few moments of weight. Especially if said musical happens to be by an intensely loved and only recently deceased artist whose genius has been loudly reinforced for over a half-century. If there was ever a time during which Woods might lean into its characters' angsty disappointments, anxieties and heartbreaks, it'd be now.

Then again, things were pretty bad during the Great Depression, but that didn't stop Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers from having the most delightful time gliding across some tastefully decorated ballroom. What makes this production similarly sublime is that it opts to be loose, broad, frothy and fun without ever cheapening the material. Audiences don't always need to reminded that they're traumatized, disillusioned, and sad. The characters in this production surely are too--they're us, after all--but they're also tough, adaptable, funny and thoroughly unwilling to let life's disappointments, crises, or even unspeakable tragedies get in their way.

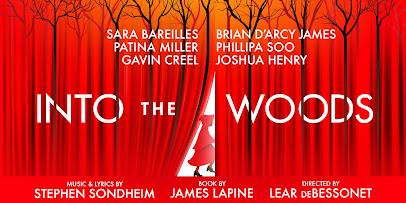

Swiftly, playfully directed by Lear DeBessonet, Into the Woods features a stellar cast of Broadway veterans, relative newcomers and some very endearing puppets. The actors lean almost consistently into life's pleasures: Julia Lester's voracious Little Red Ridinghood is most obvious (and hilarious) in this respect, but Patina Miller's Witch, for all her tsuris, does a bodily undulating dance whenever she hears Rapunzel's voice, and Sara Bareilles' headstrong and breezily independent Baker's Wife makes a lot more sense than she ever did: sure she loves her husband, but why not take a quick roll in the hay with a fatuous Prince (Gavin Creel) while your heart's still beating?

The whole cast exudes joy and makes Sondheim's complicated score sound as easy and as miraculous as breathing. I'm sure it helps to have an audience as adoring and as eager to be delighted as the one I saw the show with: just about every number threatened to bring the house down; a couple of entrances and exits did, too. A little girl danced energetically (and impressively quietly) up and down the far aisle through much of act II. I knew how she felt.

So what if all the puppeteering, joking and lightheartedness results in a breezier, less emotionally impactful--or even clear--second act? I'm not sure exactly what was going on with the Witch's departure, and none of the characters grieve for more than a split second upon learning of the deaths of loved ones. No matter: We all know pretty damned well by this point that people don't always make it out of the woods. I'm certainly willing to trade a few muted moments for a consistent reminder that joy is like oxygen, that it's futile to feel guilt about seeking it out, and that a light touch can be a magical elixir for the weary, traumatized masses. That there can be moments of such unadulterated joy in the midst of so much awful is about as profound a reminder of why we soldier on in the first place.

Go. Have fun; I hope you leave feeling a little lighter than you did when you walked in.

%20Tara%20Giordano%20(Ruby)%20in%20Hot%20Fudge%20by%20Caryl%20Churchill.JPG)

%20and%20James%20Patrick%20Nelson%20(Dog)%20in%20DOG%20PLAYS%20by%20Robert%20Chesley.JPG)