Cookies

Wednesday, February 12, 2014

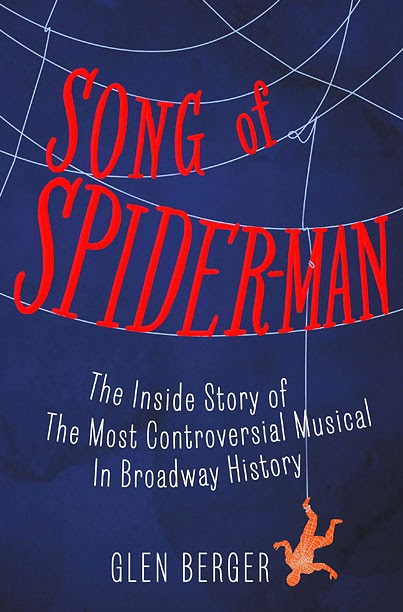

Book review: Song of Spider-Man: The Inside Story of the Most Controversial Musical in Broadway History.

No Broadway show in recent memory elicited a more potent blend of scapegoating and Schadenfreude than Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, which was conceived in 2002 by producer Tony Adams, scored by U2's Bono and The Edge, written by Glen Berger and Julie Taymor (and, later, sort of, Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa), directed by Taymor (and, later, sort of, William Philip McKinley), and which opened at the Foxwoods Theater on 14 June 2011. Between its conception and its opening night, the show went through enough trials and tribulations to make Job look like a dude who just hit a brief bad patch.

The efforts it took to get Spider-Man to the stage are the stuff of Broadway legend. It took three years to work out the creative team's contracts, and just as they were finally all being signed in The Edge's New York apartment, Tony Adams suffered a massive stroke and died. No joke. While Edge was looking around for a pen. Seriously. Rather than reading this as an omen and running, screaming, from the project, Adams' producing partner, Alan Garfinkle, took over as lead producer, but he had no Broadway experience, and the production soon ran out of money. Bono's friend, the rock impresario Michael Cohl, also chose not to run screaming from the project; instead, he came in as lead producer in 2009, just in time for the economy to tank. More money for Spider-Man was nevertheless eventually raised, and rehearsals started up again.

But Things Would Get Worse for Ozzy: Alan Cumming and Evan Rachel Wood were cast in the show only to run screaming (citing scheduling problems) a few months later. Grievous, widely reported injuries happened to various cast-members during rehearsals and early previews. Major technical problems involving the more spectacular stage effects cost millions of dollars to execute and millions more to fix, and were eventually abandoned because they never actually worked. Five different opening nights were announced and subsequently rescheduled over the course of a record-shattering (not in a good way) 182 preview performances. A major world tour that U2 embarked upon during the worst of the tech period took Bono and Edge across the world and out of close touch for weeks at a time. Eventually, there was finger-pointing, scapegoating, the assignation of blame, and the ouster of director Julie Taymor, followed by a six-week hiatus during which a team of "fixers" were brought in to retool the production. Then the law suits began (they're still happening). None of this was helped by the fact that the New York Post theater columnist Michael Riedel wrote regularly--gleefully, nastily--about the show, its mushrooming costs (initially around $23 million; eventually $75 million), and every one of its many problems. Or that the ceaseless press scrutiny helped Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark become something of an international joke. Or that jackasses like me--and many, many, many other bloggers, Tweeters, and Facebookers--took the show to task so frequently, so publicly, so snarkily. No publicity might well be bad publicity, but I would be willing to bet that the company of Spider-Man, laboring away in their bubble in a desperate attempt to get the show running and open, probably would have welcomed a little anonymity during the very worst of times.

Glen Berger clearly did; he makes this abundantly clear in his smart behind-the-scenes tell-all, Song of Spider-Man. A playwright with a young family, a successful Off-Broadway play under his belt, and a handful of television credits to his name, Berger was initially over the moon about getting the chance to work with Taymor, Bono, and Edge on a big-budget Broadway show. Can you blame him? What's more remarkable, really, is that he seems to remain enormously appreciative of all involved, despite the fact that Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark separated him from his family for months at a time, resulted in profound emotional exhaustion and blunt-force trauma to the ego, and very seriously damaged a number of close collaborative relationships, specifically his with Taymor. Berger's book brings the reader through the (initial) thrilling highs and (eventual) devastating lows that the Turn Off the Dark company experienced in the years--YEARS--that they struggled together to simply get the show to work...sort of...most of the time. Berger describes a lot of stress-related weight-loss, bickering, weeping, and puking that happens in the process.

Song of Spider-Man is not a perfect book--it's a little evasive in some respects, a little overwritten in others. There are no pictures, which I suspect would've been prohibitively expensive. Berger plays the innocent bystander a bit too often in his own recounting, and relies on italics a lot. I mean, like, repeatedly. On every page. To the point of major distraction. It's just too much. Where was his editor?

Then again, maybe the italics are an indication that Berger himself has still not quite managed to--um---rise above the emotional damage that Spider-Man caused. And really, think about this: an overuse of italics is all I can come up with to bitch about, which is saying something. Indeed, italics or no, Song of Spider-Man is a fantastic read. Not just because the story Berger is recounting is one of the more compelling ones to come out of the American commercial theater in a long time (hell, maybe ever), but because he is so adept at pacing, at explaining the collaborative process, and, perhaps most importantly, at clearly demonstrating the fact that despite the urge to point fingers and name names, no one is solely to blame when projects this big struggle as horribly as Spider-Man did. In this respect, Song of Spider-Man is not only an exciting, interesting, and compelling book, but also an exceptionally kind and even-handed one. No small feat, especially considering what a nightmare the show was.

Spider-Man was incredibly easy to make fun of, which is one of the reasons it made international headlines. The production was enormously expensive, especially during a time of serious economic downturn. It featured a team of seemingly insensitive, arrogant people who didn't know what the hell they doing. Witness the vilification, in particular, of Taymor and Bono. At times, they themselves seemed like their own worst enemies: it didn't help his case, for example, when Bono would occasionally drop by a rehearsal and spout shit about Rilke, Blake, Lichtenstein, and the Ramones to the press. Similarly, Taymor's singlemindedness and refusal to engage with the bad press--as well as the fact, let's face it, that she is a very creative and powerful director who is also a woman--made it easy for the media to depict her as an arrogant, self-involved spendthrift who didn't care about how much dough was spent or how many actors were mangled so long as she got ten seconds of one scene perfectly right.

Berger does a fine job of carefully, calmly exploding all of that easy, idle, water-cooler chatter as oversimplified bullshit. Of course Taymor cared about her cast. Of course Bono wanted to make great art. The entire overworked, demoralized, sleep-deprived, insulated, isolated company of Spider-Man did. Who wouldn't, especially after so much bad mojo, and even worse press?

Song of Spider-Man is a must-read, not only for people interested in the history of Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, but as well for people who wonder about how contemporary commercial theater gets made. No theater book I've read captures the psychology of theatermaking quite as well as this one does, or demonstrates as neatly that weird, thrilling, aggressively inward-looking creative process. Berger expertly recounts the obsessive impulse to keep working--for days, weeks, years at a time--on something you have committed to, even when you're retching from stress, shaking from exhaustion, neglecting your family, and endlessly, painfully, furiously aware of the fact that the whole world seems primed to make mincemeat of you and your work at every turn.

Song of Spider-Man is not only a deeply engaging book, but one that I was disappointed to reach the end of. I am sorry that the Spider-Man company suffered as they did, but I sure am glad that Berger lived to tell its tale. I wish Song of Spider-Man an enormous (print) run, and its author--and all of his bent but unbroken Spider-Man colleagues--big success on all future endeavors. Man, they deserve it.

Labels:

Bono,

Glen Berger,

Julie Taymor,

Spider-Man,

The Edge,

U2

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment