|

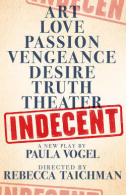

| Sullivan, Williams Photo: Joan Marcus |

Cost of Living follows two couples. In each case, one has a visible physical disability. And, in each case, the disability remains a focus of the play yet recedes to just one facet of an emotionally complex picture.

Cost of Living utilizes an almost competitive intersectionality. Who is more powerful? John (Gregg Mozgala), a white man who cannot dress or bathe himself but went to Harvard and has money and a well-developed sense of entitlement, or Jess (Jolly Abraham), his caregiver, a physically intact woman of color who went to Princeton but is broke and scared? Both have definite strengths (not always attractive) and both have definite weaknesses (not always visible). Their jousting grows amusing, and they seem to grow close, but can they ever really understand each other?

In the other couple, Ani (Katy Sullivan) is a double amputee who has turned coarse language into an art form. Eddie (Victor Williams), from whom she is separated, is terribly lonely and wants to get back into Ani's life. He offers care, and caring, but Ani is reluctant to trust him, particularly since he is still living with another woman.

Cost of Living is so involving that its flaws don't become apparent until later. The opening monologue is too long. The fact that what follows is a flashback is unclear. A major plot point--a misunderstanding--isn't totally convincing. And there's a coincidence that's hard to buy.

But it's Majok’s character studies that make Cost of Living a must-see, along with the casting of actual disabled people, one of whom is quite good (Mozgala) and one of whom is brilliant (Sullivan). In fact, the show is well worth seeing for Sullivan's performance alone.

The recent trend toward hiring disabled people to play disabled people is fabulous and important, and I hope it's not a passing fad. But real progress will be hiring disabled people to play characters not written as disabled.

And I would gladly see Katy Sullivan in pretty much anything!