Thornton Wilder won the Pulitzer Prize three times: for the novel "The Bridge of San Luis Rey" and for the plays Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth. In distinctly different ways, all three focus on the meaning of life for individuals and for humanity in general. While "The Bridge of San Luis Rey" and Our Town are quiet and subtle creations, The Skin of Our Teeth throbs with energy and noise, bursting out of theatrical conventions, time, and reality.

Cookies

Tuesday, April 26, 2022

The Skin of Our Teeth

Thursday, April 14, 2022

Penelope, Or How the Odyssey Was Really Written

I was excited to see the York Theatre Company's new musical Penelope, Or How the Odyssey Was Really Written (book and lyrics by Peter Kellogg) because I had had sooooo much fun at Desperate Measures (book and lyrics by Peter Kellogg). While I ended up enjoying Penelope, it was no Desperate Measures.

|

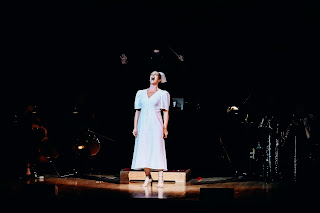

| Britney Nicole Simpson Photo: Carol Rosegg |

The first problem was the first act, which slogged along, covering the same ground over and over. While Penelope waits for Odysseus to come home, a gaggle of suitors try to woo her, meanwhile eating her out of house and home. The songs, although often entertaining and listener-friendly, do little to advance the plot, except in the most expository manner. They largely ignore the writing 101 admonition to show, not tell.

Another problem is the suitors; they come across as a group of petulant gay men in a jokey way that was tired years ago. Each gets maybe half a trait to distinguish him. They are boring company, and while they have way too much to do in terms of stage time, they have way too little to do in terms of remotely being characters. Why not have one who actually loves Penelope? Maybe have two that are a couple but need/want to marry into money and power? And maybe one who is embarrassed at being a parasite, but has no other options? Yes, this is a comedy and, yes, you don't want to focus on them too much, but they could be twice as interesting in half the time. And the feyness is just old.

The third problem is the direction, which focuses heavy-handedly on silly, which is okay in and of itself, but silly for the sake of being silly grows tiresome.

The thing with silly comedy is that it is still theatre and still benefits from calibration, characterization, and a sense of actual stakes. To me, the best comedies are the ones where you care about the characters.

Luckily, in the second act, stuff actually starts to happen. The scenes between Penelope and Odysseus work because they are actual scenes, with conflict, interaction, and, yes, actual stakes. I suspect that with the first act cut in half, no intermission, and subtler and more specific direction, Penelope could be a pretty wonderful show.

In terms of performance, the women steal Penelope. Britney Nicole Simpson is excellent and sometimes even thrilling as Penelope. She comes across as the love child of Debbie Allen and Patti LuPone, and really, could you ask for better parents? It's her Off-Broadway debut, and I suspect/hope that she has an exciting career ahead of her. Leah Hocking nails the role of Odysseus's mother, and Maria is lovely as Daphne, shepherdess of the pigs and love interest to Odysseus's son. Among the men, Ben Jacoby and Philippe Arroyo stand out as Odysseus and his son, respectively.

The music, by Stephen Weiner, is fairly generic but quite pretty, and it is well presented by the five-piece band (musical director David Hancock Turner, Gregory Jones, John Skinner, Mike Raposo, and Allison Seidner). While Kellogg's book definitely needs work, his lyrics are clever and often quite funny. James Morgan's set is attractive, and while I wish the show wasn't miked in that small theatre, Bradlee Ward's sound design is clean and well-modulated.

As it stands, Penelope's second act is a fun ride, but a much better overall show is definitely in there.

Wendy Caster

Monday, April 11, 2022

Queens Girl in the World

Friday, March 11, 2022

Anyone Can Whistle: MasterVoices

The MasterVoices' concert of Anyone Can Whistle was a lovely and poignant reminder that although we have lost Stephen Sondheim, we will always have his work. And, oh!, that work!

|

| Elizabeth Stanley Photo: Nina Westervelt |

Anyone Can Whistle is, to say the least, a problematic musical, bloated here, thin there, sometimes smart but too often cutesy. But the score includes gems: in particular, "There Won't Be Trumpets," "Anyone Can Whistle," and "With So Little to Be Sure Of." And, like all of Sondheim's work, Anyone Can Whistle rewards multiple hearings and viewings. I have known the original cast recording by heart since the late 1970s, yet I was surprised and delighted over and over again by Sondheim's brilliance, humor, and heart.

The cast of the MasterVoices concert was uneven. Elizabeth Stanley was magnetic, brilliant, moving, thrilling, superb, and fabulous. On the other hand, Vanessa Williams was little better than mediocre; frequently, she seemed uncomfortable with the music, and she lacks the presence necessary to give dimension to the Mayoress. She just wasn't interesting. Santino Fontana is always likeable, and he has a lovely voice, but his performance was bland. While Stanley prepared for and gave a full performance, Williams and Fontana seemed less prepared, and they sang songs rather than playing characters.

One of the highlights of the evening was Joanna Gleason's entrance (she narrated the show). Over 2,800 people greeted her as an old friend, roaring and clapping as she beamed with pleasure. And of course she was wonderful as the narrator.

|

| Ted Sperling, Vanessa Williams Photo: Nina Westervelt |

Ted Sperling did a nice job as director and an excellent job as conductor. The orchestra sounded terrific. The MasterVoices chorus was entertaining but underused. Weirdly enough, the sound was erratic. Carnegie Hall is famous for its acoustics, and during intermission my friend told me of sitting in the last row of the highest balcony years ago and hearing every unmiked word. I guess the miking was a problem, because the sound was sometimes murky, and occasionally crackly, with much dialogue completely lost.

Before the concert started, Sperling spoke a few words of introduction. He showed us his vocal score, given to him by Victoria Clark in 1984. It was a mistake to put Victoria Clark in our minds, because it was so easy to imagine how amazing she would have been as the Mayoress.

But the evening's two stars made it a concert well worth seeing: Stephen Sondheim and Elizabeth Stanley. They made astonishingly beautiful music together.

Wendy Caster

Monday, March 07, 2022

JANE ANGER or The Lamentable Comedie of JANE ANGER, that Cunning Woman, and also of Willy Shakefpeare and his Peasant Companion, Francis, Yes and Also of Anne Hathaway (also a Woman) Who Tried Very Hard.

|

| Amelia Workman, Talene Monahon Photo: Valerie Terranova |

I came up with a few theories:

- They had never seen first-rate camp, so were easily pleased.

- They had never seen a farce before, so were easily pleased.

My friend, who didn't find the show as annoying as I did, but also didn't like it, had another theory, perhaps the best one:

- They were friends of the cast, writer, director, and/or crew.

Wednesday, February 23, 2022

The Daughter-in-Law

The Mint Theater Company's production of D.H. Lawrence's drama, The Daughter-in-Law, so successfully evokes life in the East Midlands of England in 1912 that I was shocked when I glanced at the audience and saw people in contemporary clothing--and masks! This visit to another time and place is the cumulation of all the things that the fabulous creators at the Mint do so well: pick a compelling play, direct it with art and clarity, perform it beautifully--and provide scenery, costumes, lighting, and sound that perfectly set the scene, while also being a great pleasure to hear and see.

|

| Tom Coiner, Amy Blackman Photo: Maria Baranova |

The mining families in Lawrence's play balance two serious concerns: (1) the wear and tear of mining, with a strike looming, and (2) trying to understand, impress, escape, and love each other, while tangled in passivity, ambition, fear, and desire.

Mrs. Gascoyne's situation is ostensibly clear: she wants what's best for her grown sons. But what does that mean? And according to who? One son, Luther, a gruffly masculine man who has neither the intelligence nor the need to make much of himself, is married to Minnie, a woman he barely knows. Minnie has a small inheritance that becomes almost another character in the play, with its vibrations of power and class difference. Mrs. Gascoyne unsurprisingly has no use for Minnie.

Over the course of the play, the characters surprise themselves and each other, and sometimes us as well. The plot also takes an unexpected turn or two. It's difficult to say how much Lawrence was trying to honestly represent the reality of the people of his time and how much he was working out his mother issues, and that adds texture to the story. The end is not exactly justified by all that precedes it, and that too is intriguing. Was Lawrence trying to make a point or was it a failure of his writing?

|

| Sandra Shipley, Amy Blackman Photo: Maria Baranova |

The main thing to be said about The Daughter-in-Law is that it is a completely satisfying theatrical experience, often moving, often funny, and vivid in depicting class issues. Even the set changes are are compelling.

The Mint single-handedly keeps a whole subsection of theatre alive, rediscovering unappreciated plays and presenting them with astonishing consistency. In doing this, they also help keep alive the people of the past, as described in their present. It's so easy to think that people were different from us, partially because history and the arts have misled us, and partially because their clothing, surroundings, and values can seem so foreign. But the Mint reminds us again and again that being human has always been a messy and challenging adventure. (Yes, and that sex has always been complicated.)

CAST

- Amy Blackman

- Ciaran Bowling

- Tom Coiner

- Polly McKie

- Sandra Shipley

- Director: Martin Platt

- Sets: Bill Clarke

- Costumes: Holly Poe Durbin

- Lights: Jeff Nellis

- Sound: Lindsay Jones

- Props: Joshua Yocom

- Dialects: Amy Stoller

- Illustration: Stefano Imbert